DVS-TV was underway at the Congress Aluminium Brazing in Düsseldorf, Germany, which took place in June 2014. The interesting video report is online since July. Among other things, coverage included Solvay’s presence and an interview with Dr. Hans-Walter Swidersky.

Additional information to the Article Flux Application: Electrostatic Fluxing

In dry flux application, the flux powder is electrostatically charged (typical voltage is ~ 100 kV) and applied to a grounded work piece. An electrical field results in flux deposition of the work piece. In practice, anisotropic distribution of the electric field can influence the homogeneity of powder coverage. At edges powder may accumulate, while penetration of powder into deep/thick fin packages (e.g., in case of double row tubes) can be limited by the Faraday cage effect.

Flux powder is electrically charged in the gun. However, it loses charge relatively fast when it hits the grounded heat exchanger. Therefore adhesion of the flux on the work piece is established rather by relatively weak Van der Waals forces than by electrostatic forces. Fine flux particles adhere better on the surface – but they are more difficult to operate with in the dry powder feeding system.

The relatively fine flux particles are more difficult to handle in dry powder feed systems compared to coarser paint powders – therefore the equipment used for electrostatic flux application is adapted to meet the specific requirements. Venturi pump, hose diameter, air flow and spray nozzle suitable for flux application are designed to minimize the possibility for powder buildup and clogging in the system. Powder transport within the hose system and the spray nozzle is further enhanced by introduction of additional air streams. The direction of the powder flow should always be from top to bottom. Sharp changes in flow direction must be avoided. In critical areas additional vibration units are installed to avoid powder buildup.

There are two types of powder feed systems established on the market (see the illustrations in the article):

The first type starts with the flux powder being fluidized in a fluidization vessel by compressed air that is fed through a porous membrane at the bottom of the fluidization vessel. The air going through the flux makes it behave like a fluid, since the powder is essentially diluted with air. A pick up tube attached to a Venturi pump is extended into the fluidized flux. Powder dosage is controlled by the volume of air flow through the pump. To optimize fluidization the vessel may additionally be equipped with a stirrer.

This type of feed system works perfectly well for classic electrostatic paints powders that are easy to fluidize, however, it may be difficult to establish a stable fluidization with ’standard‘ flux powder (i.e. the flux powder quality offered for wet/slurry-based flux application).

Fluctuations in density of the fluidized bed can result in inhomogeneous spray pattern (splashing) and might be a source for flux buildup within the system.

NOCOLOK® Flux Drystatic is optimized to minimize the challenges of powder feeding, while providing sufficient fine particle fraction for good adhesion properties.

The second type of powder feed system works on the principle of feeding the powder by a rotating helix screw (see the illustrations in the article above). Because of the mechanical displacement of the flux powder from the hopper, such devices minimize fluctuations of flux powder flow.

Most mechanical type of dry flux feed systems work with standard quality NOCOLOK® Flux as well as with special ‚Drystatic‘ grade NOCOLOK® powder.

To achieve flux distribution patterns for specific process needs (e.g., higher flux loads in tube to header areas, coating from both sides of thick cores), multiple spray nozzles are arranged for deposition of the necessary flux load at different locations of the heat exchanger.

Dry fluxing booths must be equipped with a filter system to collect the overspray. The overspray material is recycled within the booth. To avoid accumulation of impurities within the recovered flux, it is necessary to take care of the booth environment (i.e. avoid dust, fumes, and high humidity level) as well as for the quality of the compressed air used. Contamination introduced by the heat exchangers or the transport belt must be prevented as well.

Due to the relatively weak flux adhesion (compared with wet- or paint- application methods), handling of dry fluxed parts should be done with special care to avoid flux fall off, especially at higher flux loads. To reduce flux fall off, some users perform electrostatic fluxing on heat exchangers with evaporative oils still present on the surfaces. Thermal degreasing in this case takes place after fluxing – just before the parts enter the brazing furnace.

Technical Information by Leszek Orman, Hans-Walter Swidersky and Daniel Lauzon

Abstract

For just as long as aluminium has been used for brazing heat exchangers, there has been a trend to down-gauging components for weight savings. The most common alloying element to achieve higher strength alloys for the purpose of down-gauging is magnesium. While magnesium additions are helpful in achieving stronger alloys, the consequence is a decrease in brazeability. This article discusses the mechanism of brazing deterioration with the addition of magnesium and proposes the use of caesium compounds as a way of combating these effects.

We split the article in five parts:

- Introduction

- Effects of Mg on the Brazing Process

- Mechanism of Magnesium Interaction with the Brazing Process

- Caesium Fluoroaluminates

- NOCOLOK® Cs Flux

NOCOLOK® Cs Flux

As a more practical means of obtaining better brazeability of Mg containing alloys, a mixture of standard NOCOLOK® Flux and caesium fluoroaluminates is used. The positive influence of Cs on brazing magnesium containing alloys was previously reported in a patent for a product where potassium fluoroaluminates were mixed with caesium fluoroaluminates [11]. However, this patent covered a rather wide ratio of potassium fluoroaluminates to caesium fluoroaluminates.

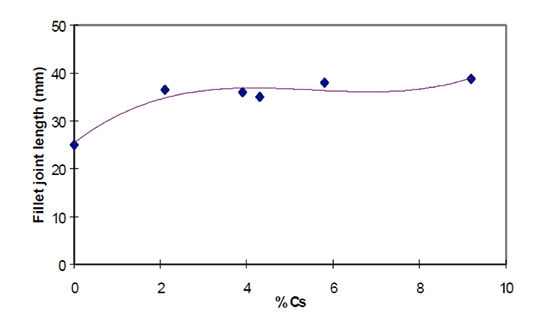

The influence of actual elemental Cs content on brazeability was investigated by Garcia et al [12]. Brazeability was determined by the length of the joint obtained in a system with a gradual increase in gap clearance (similar in concept to the one shown in Fig. 1). In their work they used 6063 alloy with a Mg content of 0.66 wt%. Their major finding is presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6: Brazeability of AA6063 alloy as a function of caesium content at flux load of 5 g/m2 [12].

As seen in Fig. 5, even a relatively low concentration of Cs in the flux mixture improves brazeability of an alloy containing 0.66 wt% Mg. An increase of Cs concentration above 2 wt% does not lead to further improvement in brazeability. In his work Garcia et al also confirmed that faster heating rates, though positive do not significantly influence brazeability.

This work led to another important finding. By brazing small sample radiators in an industrial type furnace, Garcia et al established a practical threshold for Mg content. The flux containing 2 wt% Cs is effective for brazing aluminium alloys with 0.35% to 0.5 % Mg. At lower levels of magnesium no difference between the standard flux and the 2 wt% Cs flux was observed. Brazing samples containing 0.66% of magnesium yielded leak free parts – but the brazing ratio for fins was not fully satisfactory.

This work led to the standardization of Solvay’s NOCOLOK® Cs Flux at 2 wt% Cs. By using this minimal but effective Cs concentration in the mixture, the chemical and physical characteristics are similar to the standard flux.

Summary

- Magnesium is very often added to aluminium alloys to increase strength and machinability.

- The addition of magnesium negatively influences the brazing process due to the formation of smaller fillets and the presence of porosity in the joints. This is due to (a) magnesium diffusing to the surface during the brazing cycle and forming Mg containing oxides which are more difficult to remove by the molten flux and (b) by poisoning the action of flux through the formation of K-Mg-F compounds.

- The above effect can be made less pronounced when standard NOCOLOK® Flux is mixed with a caesium aluminium fluoride complex. At a concentration of 2 wt% Cs one can observe a positive effect on aluminium alloys containing magnesium. Increasing the Cs content above 2 wt% does not yield any further increase in brazeability.

- NOCOLOK® Cs Flux works effectively for alloys containing roughly 0.3 to 0.5 wt% Mg. Depending on specific design and process conditions, Cs containing fluxes can also offer benefits for alloys containing 0.3 wt% or even less Mg. For concentrations higher than 0.5 wt% of Mg, the effectiveness of Cs compounds in non-corrosive fluxes gradually decreases.

- Pure caesium aluminium fluoride complex is effectively used for flame brazing where a lower melting point flux is required.

Download the complete article as a PDF-File.

References:

- S. W. Haller, “A new Generation of Heat Exchanger Materials and Products”, 6th International Congress “Aluminum Brazing” Düsseldorf, Germany 2010

- R. Woods, “CAB Brazing Metallurgy”, 12th Annual International Invitational Aluminum Brazing Seminar, AFC Holcroft, NOVI, Michigan U.S.A. 2007

- T. Stenqvist, K. Lewin, R. Woods “A New Heat-treatable Fin Alloy for Use with Cs-bearing CAB flux” 7th Annual International Invitational Aluminum Brazing Seminar, AFC Holcroft, NOVI, Michigan U.S.A. 2002

- R. K. Bolingbroke, A. Gray, D. Lauzon, “Optimisation of Nocolok Brazing Conditions for Higher Strength Brazing Sheet”, SAE Technical Paper 971861, 1997

- M. Yamaguchi, H. Kawase and H. Koyama, ‘‘Brazeability of Al-Mg Alloys in Non Corrosive Flux Brazing’’, Furukawa review, No. 12, p. 139 – 144 (1993).

- A. Gray, A. Afseth, 2nd International Congress Aluminium Brazing, Düsseldorf, 2002

- H. Johansson, T. Stenqvist, H. Swidersky “Controlled Atmosphere Brazing of Heat Treatable Alloys with Cs Flux” VTMS6, Conference Proceedings, 2002

- U. Seseke-Koyro ‘‘New Developments in Non-corrosive Fluxes for Innovative Brazing’’, First International Congress Aluminium Brazing, Düsseldorf, Germany, 2000

- K. Suzuki, F. Miura, F. Shimizu; United States Patent; Patent Number: 4,689,092; Date of Patent: Aug. 25, 1987

- L. Orman, “Basic Metallurgy for Aluminum Brazing”, Materials for EABS & Solvay Fluor GmbH 11th Technical Training Seminar – The Theory and Practice of the Furnace and Flame Brazing of Aluminium, Hannover, 2012

- K. Suzuki, F. Miura, F. Shimizu; United States Patent; Patent Number: 4,670,067; Date of Patent: Jun. 2, 1987

- J. Garcia, C. Massoulier, and P. Faille, „Brazeability of Aluminum Alloys Containing Magnesium by CAB Process Using Cesium Flux,“ SAE Technical Paper 2001-01-1763, 2001

EABS and Solvay Special Chemicals announce the thirteenth annual presentation of their joint technical training seminar.

Dates: 9th and 10th September 2014

Purpose of the Seminar:

This technical training seminar will be presented in English at the Conference Centre and laboratories of SOLVAY GmbH, in Hannover, Germany. It will provide information concerning the manufacturing practices commonly used for brazing operations and, in particular, will address the three fundamental aspects of the industrial-scale brazing of aluminium.

These are:

- The flame brazing of aluminium.

- The Controlled Atmosphere Brazing (CAB) of aluminium heat exchangers with non-corrosive fluxes (NOCOLOK® Flux).

- The methodology of how to ensure that the brazing process selected is, indeed, the one that represents ‘best practice’.

Here you can find the detailed seminar programme and registration.

Watch the video of the EABS Technical Training Seminar

EABS: The European Association for Brazing and Soldering

Secretariat: Secure Hold Business Centre – Studley Road – Redditch, B98 7LG, England

Telephone: ++44 (0) 1527 519 463 – Telefax: ++44 (0) 1527 518 718

e-mail: admin@eabs.org.uk – Website: www.eabs.org.uk