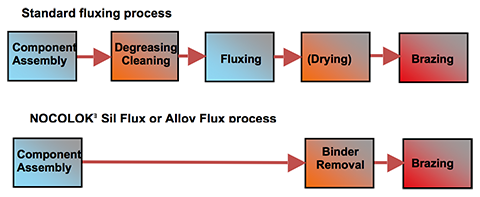

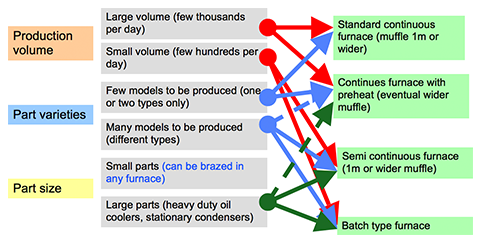

Brazing aluminum products such as radiators, condensers, evaporators, etc. for the auto industry is a mass production process. The brazing operation is generally carried out in a mesh belt furnace under a nitrogen atmosphere and is commonly known as ‘CAB’ – Controlled Atmosphere Brazing.

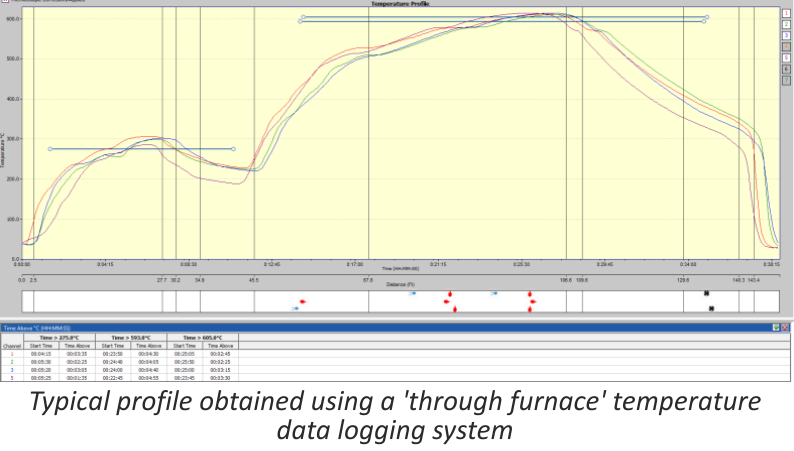

Accurate temperature measurement of the product throughout the furnace can be critical. Using a ‘through furnace’ temperature profiling system to measure product temperature is common practice within the industry, and the benefits are well established. There are also some known disadvantages to using these types of systems and here we look at recent developments to overcome these problems.

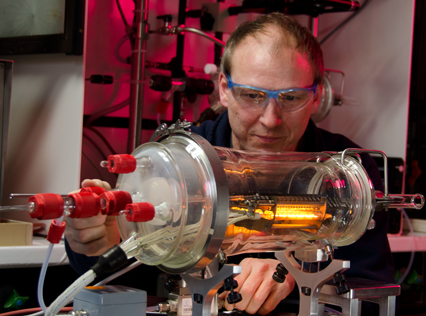

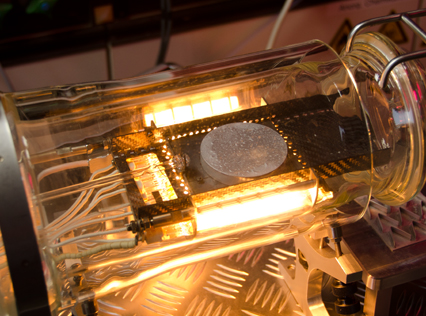

The ‘through furnace’ profiling system measures temperature by connecting thermocouples at specific points on the product which feed temperature information back to the data logger. The data logger is protected from the heat of the furnace by a ‘hot box’ or thermal barrier, allowing the system to travel through the furnace together with the product, storing valuable temperature data which is analysed at the end of the process using specialized software.

As previously stated the benefits of using temperature profiling systems are well known, however there are some disadvantages, these are:

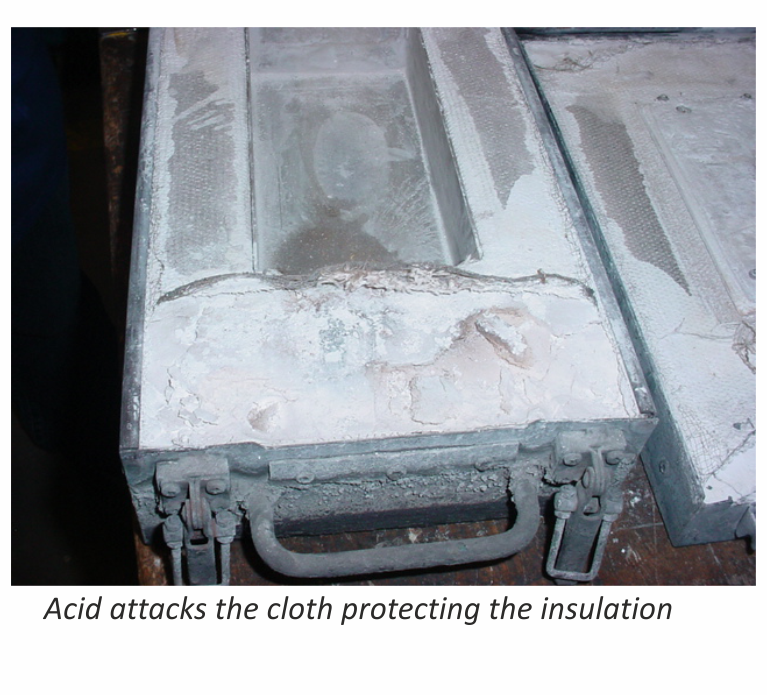

- The thermal barrier normally has a very limited life span as parts of the insulation package are subject to acid attack from chemicals within the flux.

- Oxygen can leak from within the thermal barrier while it is in the furnace, potentially contaminating the nitrogen atmosphere.

A. Acid attack

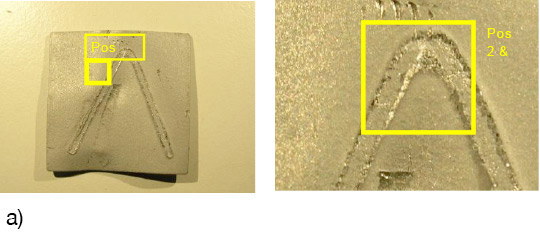

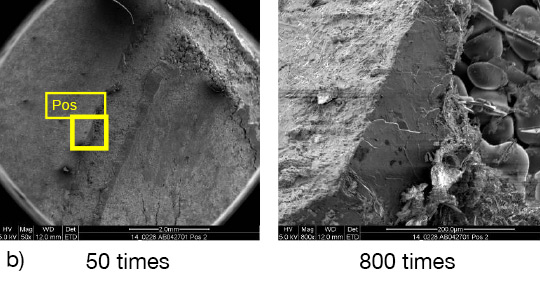

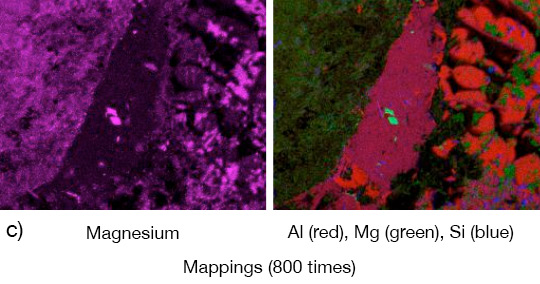

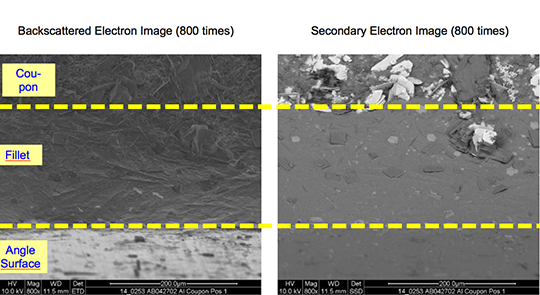

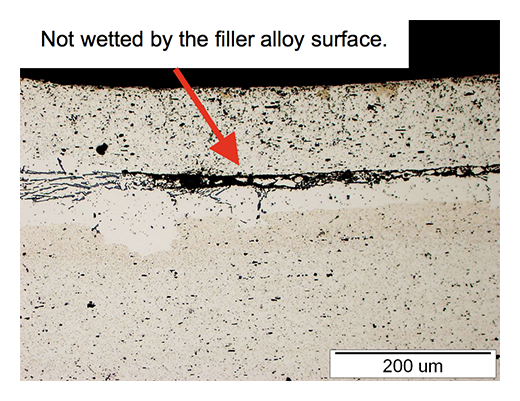

During the braze cycle, moisture in the air inside the ‘hot box’ or thermal barrier will combine with chemicals in the brazing flux to form hydrofluoric acid which attacks the high temperature cloth covering the microporous insulation. Once this cloth begins to break down, the unprotected insulation at the entrance to the ‘hot box’ wears away increasing the aperture where the thermocouples enter. This allows heat in, potentially damaging the data logger, and lets oxygen escape into the furnace atmosphere, which may affect braze quality.

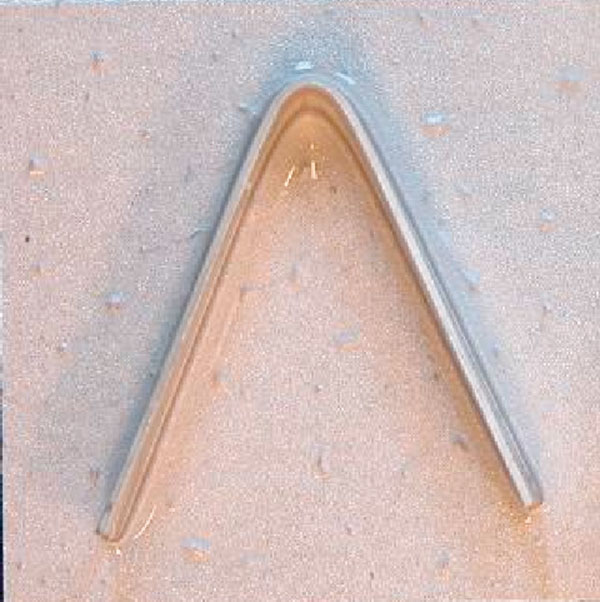

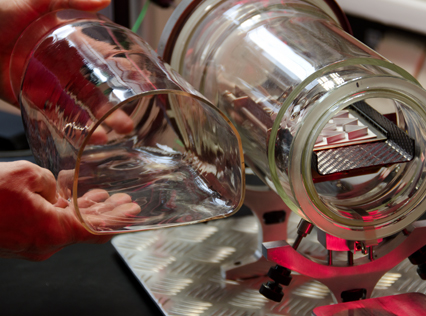

The life of this type of thermal barrier is severely reduced leading to high maintenance costs. The solution uses a robust ‘drawer’ design rather than the traditional ‘clam shell’ type.

This eliminates exposure of the high temperature cloth to the aggressive flux atmosphere, and significantly increases the life of the barrier. This new type of thermal barrier has been used in daily production since April 2011 at many leading automotive parts suppliers, with one major North American auto manufacturer reporting over two thousand uses without any wear problems.

B. Oxygen leakage

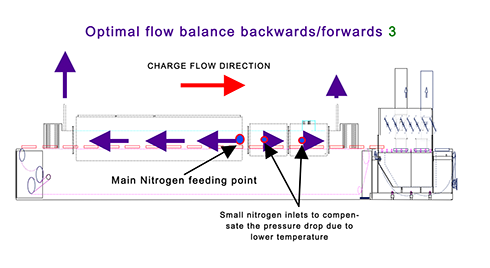

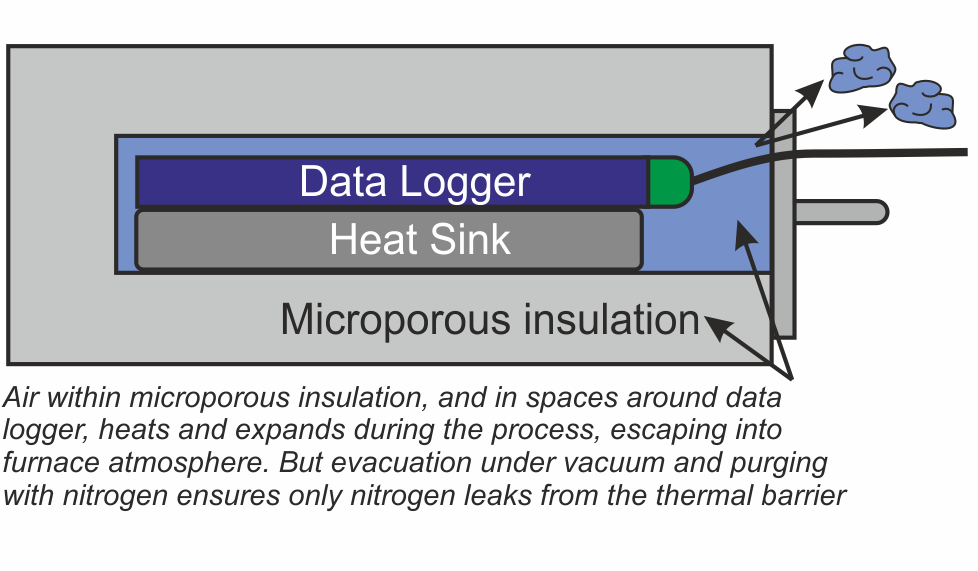

Whether the thermal barrier is a ‘clam shell’ or ‘drawer’ type it will contain air. As the system travels through the furnace the air begins to warm up and expands. As it expands it begins to leak out into the furnace atmosphere, which may be an issue to some users.

There are two areas within the thermal barrier where air will accumulate – within the microporous insulation, and in the spaces around the data logger and heat sink. A ‘two stage’ approach has been developed to remove this air.

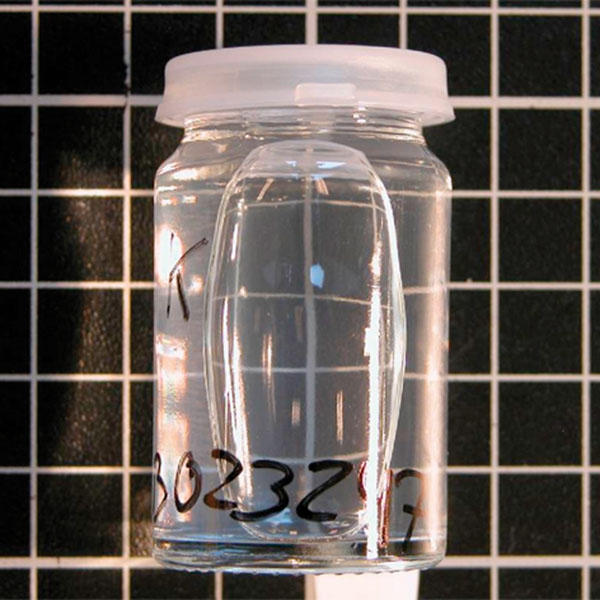

Firstly eliminating the air deep within the microporous insulation is achieved by heating the whole thermal barrier or ‘hot box’ in a high vacuum, then back filling with nitrogen. This operation is carried out as the last stage in the manufacturing process.

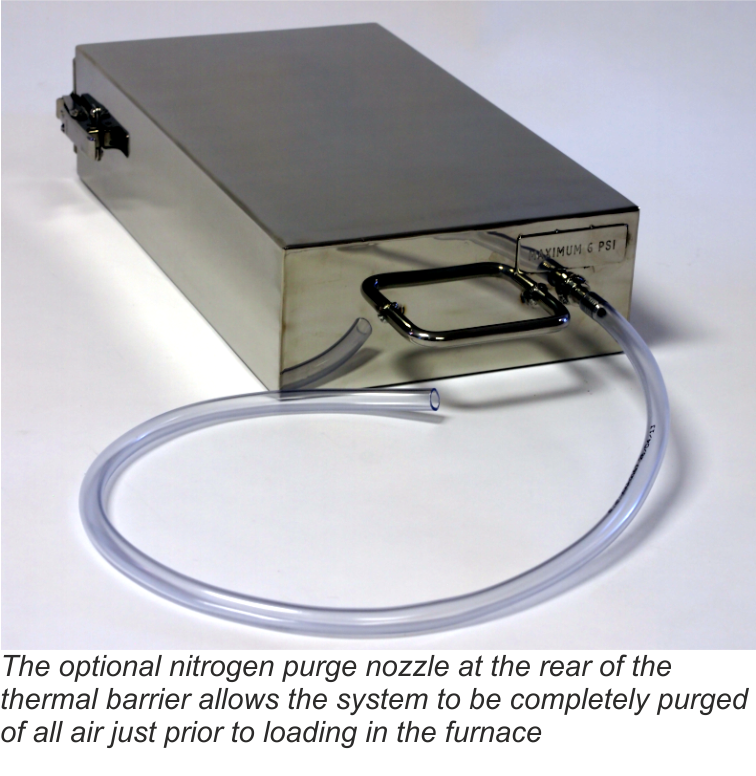

Secondly, as an option for users with sensitive processes, all remaining air in the spaces around the data logger can be purged with low pressure nitrogen just prior to placing the system in the brazing furnace.

The nozzle for the nitrogen purge has been designed to allow free flow of the gas through the barrier, but by use of strategically placed internal ‘baffles’, heat penetration is minimized during the brazing process.

Conclusion

Although using a profiling system to monitor the product temperature in a CAB furnace has generally been considered high maintenance, it was judged that the value of the data obtained was worth the extra cost. However through careful system design a solution has been engineered that successfully overcomes these problems, saving maintenance costs and allowing the ‘hot box’ temperature profiling system to be used on a more regular basis.

Dave Plester, Director

Phoenix Temperature Measurement

www.phoenixtm.com

sales@phoenixtm.com